When you need dialysis, your body relies on a reliable gateway to get cleaned. This gateway is called a dialysis access. It’s not just a tube or a needle site-it’s your lifeline. And how well it works can mean the difference between months of smooth treatments and years of hospital visits, infections, and complications. There are three main types: arteriovenous (AV) fistulas, AV grafts, and central venous catheters. Each has its own pros, cons, and care rules. Knowing which one you have-and how to look after it-isn’t optional. It’s essential.

Why AV Fistulas Are the Gold Standard

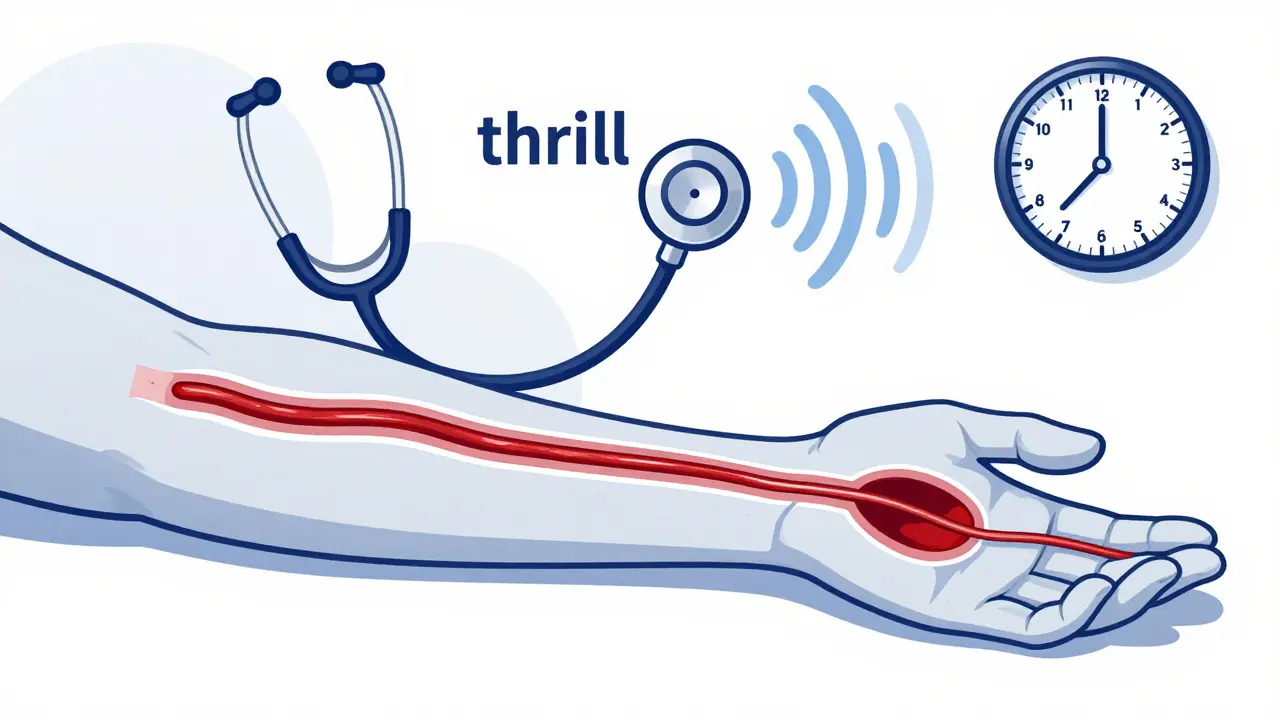

An AV fistula is made by surgically connecting an artery directly to a vein, usually in your forearm. This isn’t just a quick fix-it’s a long-term solution. After surgery, your vein has to grow stronger and thicker over 6 to 8 weeks before it can be used. That waiting period is frustrating, but it’s worth it. Once mature, a fistula can last for decades. Many people use theirs for 10, 15, even 20 years without major issues. Fistulas have the lowest risk of infection and clotting compared to other access types. Studies show that people on dialysis with a fistula have a 36% lower risk of dying each year than those using a graft, and over 50% lower risk than those with a catheter. That’s not a small difference. It’s life or death. The National Kidney Foundation calls fistulas the gold standard for a reason: they’re safer, last longer, and cost less over time. You’ll learn to check your fistula daily by feeling for a vibration-called a “thrill”-or listening for a whooshing sound with a stethoscope. That’s your body telling you blood is flowing properly. If the thrill disappears, call your clinic right away. Clots can form fast, and early detection saves the access.When a Fistula Isn’t Possible: AV Grafts

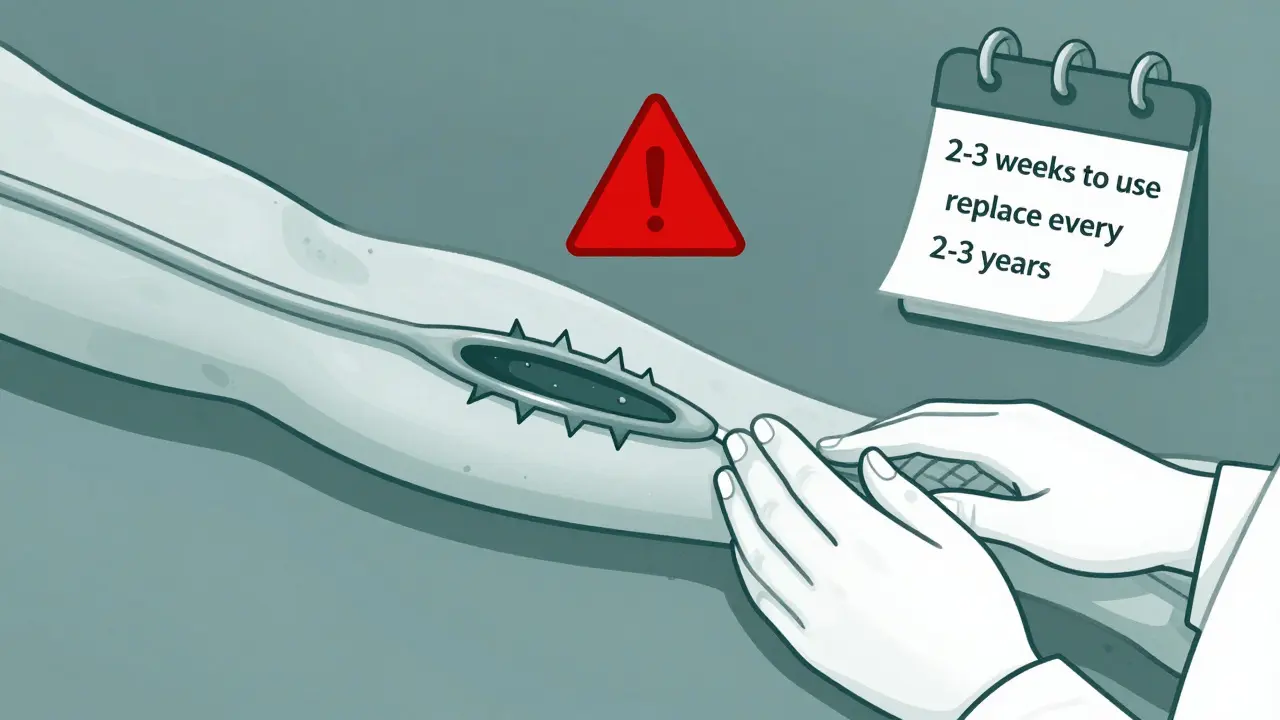

Not everyone’s veins are strong enough for a fistula. If your blood vessels are too small, scarred, or weak from diabetes or high blood pressure, your doctor may recommend an AV graft instead. This is a synthetic tube, usually made of a soft plastic called PTFE, that connects an artery to a vein. Unlike a fistula, it doesn’t need to mature naturally. You can start dialysis on it in just 2 to 3 weeks. But there’s a catch. Grafts are more prone to clots and infections. About 30 to 50% of grafts need some kind of intervention within the first year-whether it’s a procedure to clear a clot, repair a narrowing, or replace the graft entirely. They don’t last as long either. Most need replacement every 2 to 3 years. Grafts are easier to feel and check than fistulas because they sit closer to the skin. You’ll still monitor for thrill and swelling, but you might also notice the graft feels firmer or looks more raised. If it becomes tender, red, or warm, don’t wait. That could mean an infection is setting in. Grafts are a good backup, but they’re not a replacement for a healthy fistula.Catheters: Temporary, But Sometimes Permanent

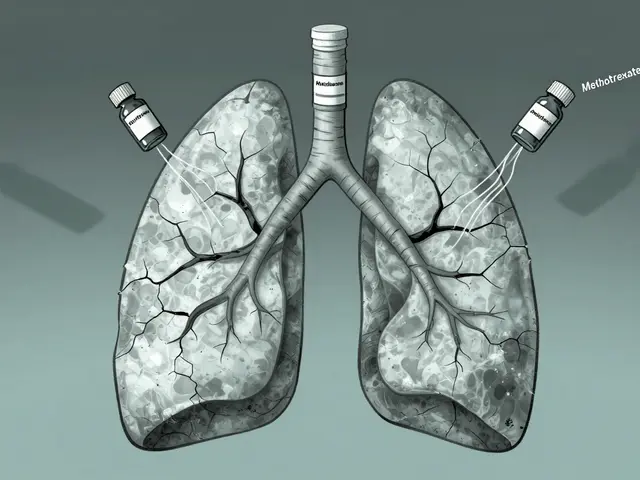

Central venous catheters are soft, flexible tubes inserted into a large vein in your neck, chest, or groin. They work immediately. That’s why they’re often used when someone needs dialysis right away-before a fistula or graft can be ready. But they’re not meant to be permanent. Catheters come with big risks. They’re the leading cause of bloodstream infections in dialysis patients. One study found that catheter use leads to over 28 extra fatal infections per 100,000 patient-years compared to fistulas. Every time you shower or bathe, you have to cover the catheter site with waterproof dressing. Even then, water can sneak in. Many patients report feeling trapped-no swimming, no hot tubs, no relaxing baths. Catheter care is intense. You or your caregiver must clean the exit site daily with antiseptic, change the dressing every time it gets wet or dirty, and follow strict sterile technique when connecting to the dialysis machine. One slip-up can lead to sepsis. That’s why doctors try to remove catheters as soon as a fistula or graft is ready. Still, some people can’t have a fistula or graft. Their veins are too damaged. In those cases, a catheter becomes their long-term option. Even then, the goal is to reduce complications: use antibiotic-coated catheters, get regular blood tests for infection, and never skip cleaning.

How to Care for Your Access Every Day

No matter what type of access you have, daily checks are non-negotiable.- For fistulas: Feel for the thrill every day. Check for swelling, bruising, or a new lump. Avoid wearing tight clothing or sleeping on that arm. Don’t let anyone take your blood pressure or draw blood from that arm.

- For grafts: Same as fistulas-check the thrill. Also look for signs of bulging or skin thinning. Grafts can develop aneurysms if needles are repeatedly placed in the same spot. Rotate needle sites during dialysis to prevent this.

- For catheters: Clean the exit site daily with chlorhexidine. Keep the cap tightly closed when not in use. Never touch the end of the catheter. If the dressing gets wet, change it immediately. Report fever, chills, or redness around the site right away.

What Can Go Wrong-and How to Prevent It

Even the best access can fail. Here’s what to watch for:- Clotting: The most common problem. If your thrill disappears, your dialysis machine won’t work properly. Clots can form in minutes or over days. Regular blood flow monitoring helps catch it early. New wireless sensors, approved in 2022, can alert you to low flow before a clot forms.

- Infection: Especially dangerous with catheters. Signs include fever, chills, redness, pus, or swelling. Never ignore these. Infections can spread to your heart valves and become life-threatening.

- Aneurysm: A bulge in the vein or graft wall from repeated needle punctures. If you notice a balloon-like lump, tell your team. It can rupture or become infected.

- Narrowing (stenosis): Scar tissue can build up inside the vessel, slowing blood flow. This often shows up as longer dialysis times or poor clearance. A simple ultrasound can spot it.

What’s Changing in Dialysis Access

The field is evolving. In 2022, the FDA approved the first wireless sensor for monitoring fistula blood flow. It’s small, worn on the skin, and sends alerts to your phone if flow drops. Early results show a 20% reduction in clots. Researchers are also testing bioengineered blood vessels-like Humacyte’s human acellular vessel-that could replace synthetic grafts. These are made from donor tissue stripped of cells, so your body doesn’t reject them. They’re still in trials, but they could be a game-changer for patients with no usable veins. Meanwhile, efforts to reduce disparities continue. Black patients are still 30% less likely to get a fistula than White patients-even when they’re medically eligible. Dialysis centers are now using standardized protocols to ensure everyone gets the same access options. The goal by 2030? Keep fistulas as the top choice for 65-70% of patients. Catheter use should drop below 15%. That’s not just a number-it’s thousands of lives saved from infection, hospitalization, and early death.What You Can Do Today

If you’re starting dialysis:- Ask for a vein mapping ultrasound before surgery. It shows which vessels are strong enough for a fistula.

- Push for a fistula if you’re eligible. Don’t accept a graft or catheter unless there’s no other option.

- Get trained on access care. Practice until it’s second nature.

- Check your access daily. Know your thrill. Know your signs of trouble.

- Speak up if something feels off. Don’t wait for your next appointment.

- Don’t assume your access is fine just because it’s worked so far. Get regular ultrasounds.

- Ask if you’re eligible for a new access if yours is failing. A fistula can still be created, even after grafts or catheters.

- Encourage others to learn. Share your experience. You might save someone from a catheter.

Can I still exercise with a dialysis fistula?

Yes, but be smart. Light to moderate exercise like walking, swimming, or cycling is encouraged. Avoid heavy lifting or activities that put direct pressure on your access arm. Don’t do push-ups or bench presses with that arm. Talk to your care team about safe exercises based on your access type.

How long does it take for a fistula to mature?

Typically 6 to 8 weeks, but it can take up to 12 weeks for some people. Factors like age, diabetes, smoking, and vein health affect how quickly it matures. If it hasn’t matured after 3 months, your doctor may need to check for narrowing or other issues.

Can I shower with a catheter?

Yes, but only with a waterproof dressing approved by your dialysis team. Never let water touch the catheter site. Use a plastic wrap or commercial waterproof cover. If the dressing gets wet, change it immediately. Showers are safer than baths-never soak in water with a catheter.

Why do some people need multiple grafts?

Grafts are more likely to clot or get infected than fistulas. About half need a procedure within the first year to clear a blockage or fix a narrowing. If a graft fails completely, another one can be placed elsewhere. But each failure increases the risk of future problems. That’s why fistulas are preferred.

Is it safe to have blood pressure taken on my access arm?

No. Never. Blood pressure cuffs can crush or damage your access, leading to clotting or rupture. Always tell medical staff not to use your access arm for BP, IVs, or blood draws. Wear a medical alert bracelet that says “No Blood Pressure or Venipuncture on Access Arm.”

paul walker

This is life-saving info. I wish I'd known all this when I started dialysis. Check your thrill daily. No excuses. Your life depends on it.

Kacey Yates

I'm a nurse and I've seen too many patients ignore the thrill. One guy waited 3 days after it disappeared. By the time he came in his fistula was dead. Don't be that guy. Feel it every morning like brushing your teeth.

LOUIS YOUANES

The fact that we're still using synthetic grafts in 2025 is a testament to how broken the healthcare system is. Real innovation is happening in labs but hospitals still treat patients like disposable widgets. Fistulas are cheaper and better but insurance won't cover the prep time. It's all about profit not outcomes.

Keith Oliver

You think catheters are bad wait till you see what happens when the dialysis center runs out of sterile kits. I had to use a reused cap once because the nurse said we were 'in a pinch'. Next day I had a fever. They called it 'unrelated'. Bullshit. That's why I wear my own gear now.

Laura Arnal

My mom's fistula is 14 years old and still going strong. She checks it every morning with her stethoscope like it's her morning coffee. She says it's the only thing keeping her alive and she treats it like royalty 😊

Robin Keith

The entire paradigm of dialysis access is predicated on a fundamental misunderstanding of the human body as a machine to be maintained rather than a living system to be nurtured. We've reduced the vascular system to a series of pipes to be patched and probed, ignoring the ontological reality of biological autonomy. The fistula isn't just a conduit-it's an existential assertion of continuity.

ryan Sifontes

They say catheters are temporary but no one tells you how many people end up stuck with them forever. I've been on one for 5 years. My wife won't let me touch the sink without gloves. I can't even hug my grandkids without worrying about infection. This isn't medicine. It's a prison.

Jasneet Minhas

Interesting how the article mentions Black patients are 30% less likely to get fistulas... but doesn't mention that most dialysis centers in poor neighborhoods don't even have vascular surgeons on staff. It's not bias-it's infrastructure collapse. And yes I'm from India where this exact thing happens with diabetes care.

Eli In

I'm from the Philippines and we don't have access to wireless sensors or bioengineered grafts. But we do have community nurses who teach patients how to feel for the thrill using their fingers. Simple. Human. Effective. Maybe the real innovation isn't tech-it's care.

Megan Brooks

There's an ethical dimension here that's rarely discussed. The burden of daily vigilance falls entirely on the patient. We expect someone with chronic illness to become a medical technician overnight. Is this really justice? Or just efficiency disguised as empowerment?

Paul Adler

I've had a fistula for 8 years. I never thought I'd make it this long. The hardest part wasn't the needles or the fatigue. It was learning to trust my own body again. That thrill? It's not just blood flow. It's proof I'm still here.

Doug Gray

The FDA approved that wireless sensor in 2022... but insurance still won't cover it unless you're on Medicare Advantage. And even then only if your nephrologist fills out 17 forms. We're optimizing for bureaucracy not outcomes. The tech exists. The will doesn't.

Pawan Kumar

This is all a distraction. The real issue is the government's hidden agenda to reduce dialysis spending by making patients responsible for their own survival. They don't care if you live or die-they care about the cost per patient-year. The fistula is just the latest tool in the arsenal of neoliberal healthcare reform.

Write a comment