Every year, millions of older adults take medications they no longer need. Some were prescribed years ago for a condition that’s now resolved. Others are copies of copies-refilled automatically, never questioned. For many seniors, the medicine cabinet is more crowded than the pantry. And that’s not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous.

Why More Medicines Isn’t Better

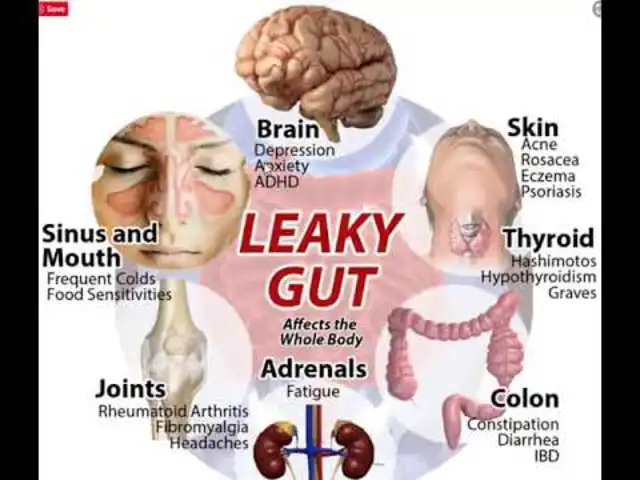

It’s easy to assume that more drugs mean better care. But for seniors, that logic falls apart. Taking five or more medications-what doctors call polypharmacy-is now the norm for nearly half of adults over 65 in the U.S. That’s up from just 14% in 1994. And while some of those pills are essential, many aren’t. The problem isn’t just the number. It’s the risk. Older bodies process drugs differently. Kidneys slow down. Liver function declines. Muscle mass drops. All of this means medications stick around longer, build up in the system, and can cause side effects that look like aging-but aren’t. Dizziness? Could be a blood pressure pill. Confusion? Maybe a sleep aid. Falls? Often tied to sedatives or anticholinergics. These aren’t inevitable parts of getting older. They’re often side effects of medicines that should have been stopped.What Is Deprescribing?

Deprescribing isn’t just stopping meds. It’s a careful, planned process of reducing or removing drugs that no longer help-or might be hurting. The term was first defined in 2003 by an Australian doctor who saw how often elderly patients were drowning in pills. Since then, it’s become a formal part of geriatric care. Think of it like this: when a doctor prescribes a new drug, they don’t just hand it over and walk away. They explain why, set goals, watch for side effects, and adjust. Deprescribing does the same thing-but backwards. It asks: Is this medicine still doing what it’s supposed to? If not, and if the risks outweigh the benefits, it’s time to stop. This isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about precision. One study showed that when deprescribing was done right, adverse drug events dropped by 17% to 30%. Hospital readmissions fell by up to 25%. Quality of life improved-without making chronic conditions worse.When It’s Time to Talk About Stopping

There are clear moments when a medication review should happen. Don’t wait for a crisis. Look for these signs:- New symptoms appear. If your loved one suddenly feels dizzy, confused, weak, or has unexplained falls, one of their meds might be the cause. These aren’t normal aging signs-they’re red flags.

- Life goals have changed. If someone has advanced dementia, is in end-stage heart failure, or can no longer get out of bed, the goal shifts from long-term prevention to comfort and quality of life. Drugs meant to prevent heart attacks or diabetes complications years from now don’t make sense anymore.

- High-risk drugs are still in use. Certain medications are known to be dangerous for seniors. The Beers Criteria, updated regularly by the American Geriatrics Society, lists drugs like benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium, Xanax), anticholinergics (e.g., Benadryl, some bladder pills), and long-term proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole. These should be reviewed at least once a year.

- Preventive meds are being taken for no clear reason. Statins for someone with limited life expectancy? Blood thinners for someone who rarely leaves the house? Aspirin for primary prevention in someone over 70 with no history of heart disease? These are common examples where the benefits are tiny and the risks-like bleeding-are real.

Who Should Be Involved?

Deprescribing isn’t something a patient should do alone. It’s a team effort. The best results come when doctors, pharmacists, and families work together. Clinical pharmacists are especially valuable. They’re trained to spot drug interactions, outdated prescriptions, and unnecessary duplicates. In one study, pharmacist-led reviews cut inappropriate meds by up to 40% in just six months. Many hospitals and community clinics now offer free medication reviews-ask your local pharmacy or senior center. Family caregivers play a key role too. They’re often the ones who notice changes in behavior, appetite, or energy. They can keep track of what’s being taken, when, and how the person feels after a change. Keep a written list of every pill, supplement, and over-the-counter drug. Include dosages and why it was prescribed. Bring it to every appointment.How It’s Done-Step by Step

Deprescribing isn’t a one-time event. It’s a process:- Review the full list. Get every prescription, OTC drug, vitamin, and herbal supplement. Don’t leave anything out. Even a daily aspirin or melatonin can interact.

- Identify the targets. Use tools like the Beers Criteria or STOPP guidelines to flag high-risk or low-benefit drugs. Focus on ones with the highest risk-to-benefit ratio.

- Start with one. Never stop multiple drugs at once. You won’t know which change caused a reaction. Pick the most likely culprit-maybe a sleeping pill or an old antidepressant.

- Plan the taper. Some drugs can be stopped cold. Others need to be lowered slowly to avoid withdrawal. For example, stopping a benzodiazepine too fast can cause seizures. A doctor or pharmacist will guide the pace.

- Monitor closely. After stopping, watch for two things: return of original symptoms (which might mean the drug was still needed) or new symptoms (which might mean the drug was causing harm). Keep notes. Call the doctor if anything changes.

- Reassess in 4-6 weeks. Did the person feel better? More alert? More steady on their feet? If yes, you’re on the right track. If not, you may need to reconsider.

Common Myths About Stopping Meds

Many families are afraid to stop meds because of old beliefs:- Myth: "If it was prescribed, it must be necessary." Truth: Doctors prescribe based on the best info at the time. Conditions change. Guidelines update. A drug that helped ten years ago might now be doing more harm.

- Myth: "Stopping could make things worse." Truth: Sometimes it does-briefly. But often, the side effects were already making things worse. Withdrawal symptoms are usually short-lived and manageable with proper planning.

- Myth: "It’s easier to just keep taking them." Truth: More pills mean more trips to the pharmacy, more costs, more confusion, more risk of mistakes. Simplifying regimens saves time, money, and stress.

What’s Being Done to Help?

The system is slowly catching up. The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has found that pharmacist-led interventions and electronic alerts in electronic health records reduce inappropriate prescribing. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now track deprescribing as part of quality care metrics. Organizations like deprescribing.org offer free, evidence-based guides for common drugs-PPIs, sleep aids, antipsychotics, and more. Each guide includes a step-by-step plan, patient handouts, and even short videos to help families understand the process. Some clinics now use AI tools to flag high-risk prescriptions during routine visits. These aren’t replacements for human judgment-they’re assistants that remind doctors: "This patient is 82, has dementia, and is on five sedatives. Are we still trying to prevent a heart attack 15 years from now?"What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for a formal review. Start now:- Ask your doctor: "Is this medication still right for me-or for my loved one-given how things are now?"

- Bring the full list of meds to every appointment. Include vitamins and supplements.

- Ask: "What are we trying to prevent or treat with this drug? What happens if we stop it?"

- Don’t refill a prescription without reviewing it first. Many pharmacies auto-fill refills. Say no if you’re unsure.

- Use tools like deprescribing.org to look up guidelines for specific drugs.

It’s Not About Cutting-It’s About Caring

Deprescribing isn’t about taking away care. It’s about giving back control. For seniors, fewer pills often mean more energy, fewer falls, clearer thinking, and better sleep. It means living well-not just surviving with a long list of drugs. The goal isn’t to be pill-free. It’s to be rightly medicated. Every drug should have a purpose. If it doesn’t, it’s time to talk about stopping.Can I just stop my meds if I think they’re not helping?

No. Stopping some medications suddenly can be dangerous. Drugs like blood pressure pills, antidepressants, or anti-seizure medications need to be tapered slowly under medical supervision. Always talk to your doctor or pharmacist before making any changes.

How do I know if a medication is no longer needed?

Ask these questions: Was this drug prescribed for a condition that’s now resolved? Is it meant to prevent something far in the future, but the person’s life expectancy is shorter? Does it cause dizziness, confusion, or fatigue? If you answer yes to any of these, it’s worth reviewing. Use tools like the Beers Criteria or visit deprescribing.org for guidance.

Are over-the-counter drugs included in deprescribing?

Yes. Many seniors take OTC drugs daily-like antacids, sleep aids, or pain relievers-without realizing they can be harmful. Benadryl, for example, is an anticholinergic linked to memory problems. Long-term use of PPIs like omeprazole increases risk of bone fractures and infections. All medications, prescription or not, should be reviewed.

Will stopping meds make my condition worse?

Sometimes symptoms return briefly after stopping a drug, but that doesn’t always mean the drug was necessary. Often, the side effects were masking other issues. For example, a sleep aid might make someone feel rested, but the real problem could be pain or anxiety. Stopping the drug can reveal the true cause-and lead to a better solution.

Is deprescribing only for people in nursing homes?

No. Most seniors live at home, and that’s where deprescribing matters most. Home-dwelling seniors often manage their own meds, with little oversight. That’s why it’s critical to review prescriptions regularly-even if you feel fine. Polypharmacy is just as dangerous in a house as it is in a facility.

Ruth Witte

I literally just helped my grandma cut down from 12 meds to 5 😭 She’s sleeping through the night, not falling in the bathroom, and even started gardening again. 🌿💊 #DeprescribingSavesLives

Noah Raines

Y’all act like doctors are saints. Nah. They’re overworked, underpaid, and get paid to prescribe. My pops was on statins for 15 years with a 0.1% risk reduction. He stopped. Still alive. No heart attack. Coincidence? I think not.

Katherine Rodgers

so like... the pharma bros wrote the beers criteria? and the drs just copy-paste? and now we're all supposed to be like 'oh wow this article is so deep'??? 🤡

Lauren Dare

The term 'deprescribing' is a misnomer. It implies a reversal of therapeutic intent, when in fact, it's a recalibration of risk-benefit profiles within a geriatric pharmacokinetic framework. Also, your OTC section is underdeveloped. Antihistamines are not 'sleep aids'-they're CNS depressants with anticholinergic burden. Please consult the 2023 AGS Beers Criteria update.

Gilbert Lacasandile

I’ve been telling my mom for years to get her meds reviewed. She’s 81, on 8 prescriptions, and still takes Benadryl for allergies. She’s always tired, always confused. I’m so glad this is getting attention. My dad’s been gone 3 years, but I still think about how he was just... fading. Maybe it was the meds.

Lola Bchoudi

Let’s normalize medication reconciliation as a routine part of annual wellness visits. Pharmacists should be mandatory participants. And insurance should cover it. This isn’t optional care-it’s harm reduction. Your grandma’s fall? Your uncle’s dementia? Often, it’s polypharmacy in disguise. Let’s stop treating symptoms and start treating the system.

Morgan Tait

I’ve seen this before. The government, Big Pharma, and the AMA are all in cahoots. They want seniors to stay medicated because it keeps the system running. They don’t want you to know that natural remedies like turmeric, magnesium, and sunlight can fix what pills can’t. They’re scared you’ll find out. That’s why they call it 'deprescribing'-to make it sound scientific. It’s not. It’s control.

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

The proposition that deprescribing constitutes a legitimate clinical intervention is, in the main, predicated upon a conflation of correlation and causation. The statistical reductions in adverse events cited are not sufficiently controlled for confounding variables such as socioeconomic status, baseline health literacy, or caregiver involvement. One must, therefore, remain circumspect.

Taya Rtichsheva

my babcia stopped all her meds and now she dances in the kitchen at 3am. i dont know if its better but shes happy and thats what matters

Christian Landry

I just asked my pharmacist to review my 72-year-old dad’s list. She found 3 duplicates and a pill that was prescribed for a UTI in 2018. We’re cutting one this week. Feels good to actually be in charge for once 😊

Katie Harrison

I’m a nurse. I’ve seen too many elderly patients on 10+ medications, all for conditions that are now irrelevant. One woman was on a beta-blocker for a heart rhythm that resolved 7 years ago. She was dizzy all the time. We stopped it. She walked without a cane within a month. This isn’t radical. It’s basic.

Mona Schmidt

The concept of deprescribing is not new, but its institutionalization is overdue. We must prioritize patient autonomy and functional outcomes over algorithmic adherence. A 90-year-old with advanced dementia does not need a statin to prevent a myocardial infarction they will never live to experience. Ethical prescribing requires contextualization, not automation.

Guylaine Lapointe

This article is so painfully obvious it’s almost insulting. Of course people are on too many meds. Of course they’re falling. Of course they’re confused. We’ve turned healthcare into a vending machine. Push button. Get pill. No questions asked. And now we’re surprised when the machine breaks? Wake up.

Sarah Gray

This is what happens when you let influencers write medical guidelines. The Beers Criteria? A glorified checklist. Real medicine requires nuance, not bullet points. And don’t get me started on 'deprescribing.org'-it’s not a peer-reviewed journal. It’s a blog with a .org domain.

Michael Robinson

We give people pills to fix problems we don’t want to see. Dizziness? Pill. Sleepless? Pill. Sad? Pill. But what if the problem isn’t the body? What if it’s loneliness? Boredom? No one to talk to? Maybe the real medicine isn’t in the bottle-it’s in the conversation.

Kathy Haverly

Oh great. Another feel-good article that ignores the fact that 90% of seniors can’t even read the labels. You think they’re going to 'review' their meds? They’re taking whatever’s in the pill organizer. The real problem isn’t polypharmacy-it’s a healthcare system that treats elderly people like passive containers for drugs.

Andrea Petrov

I know what’s really going on. The FDA, Medicare, and the AMA are all pushing this 'deprescribing' thing because they’re trying to cover up how many seniors are dying from drug interactions. They don’t want you to know that the 'side effects' they list are actually the leading cause of death in people over 75. They call it 'polypharmacy' to make it sound like a choice. It’s not. It’s negligence.

Suzanne Johnston

There is a quiet dignity in reducing the chemical burden of aging. To be rid of unnecessary pills is not to reject medicine, but to reclaim agency. I have watched my mother, once a woman of sharp wit and brisk walks, become a shadow of herself under the weight of seven daily medications. When one was removed-the anticholinergic for 'bladder control'-her eyes returned. Not because of magic. Because she was finally seen.

Graham Abbas

I cried reading this. My dad was on 11 meds. We stopped 4. He started humming again. He remembered my name. He didn’t fall for 8 months. I didn’t know he’d been so tired. I thought it was just... old age. Turns out, it was just pills. I wish I’d known sooner.

Haley P Law

I just told my 80-year-old aunt to stop her omeprazole. She said, 'But my doctor said I need it!' I said, 'So did they say you need to take it for 12 years?' She paused. Then said, 'I think I’ve been taking it since 2011.' ...I’m not her doctor. But I’m her niece. And I’m done pretending 'doctor said so' is enough.

Write a comment