There’s no such thing as a vaccine generic-not really. Unlike pills for high blood pressure or antibiotics, you can’t just copy a vaccine, swap out a few ingredients, and call it the same. Vaccines aren’t chemicals. They’re living systems. They’re grown in cells, purified under strict conditions, and packed in ultra-cold environments. Even if you have the formula, you don’t have the factory. And that’s why billions of people still wait for shots while others get boosters.

Why Vaccines Can’t Be Generic Like Pills

Generic drugs work because they’re simple molecules. If you know the chemical structure, you can recreate it in a lab with standard equipment. The FDA has a clear path for that: the ANDA process. It’s been around since 1984. Generic versions of drugs like metformin or lisinopril cost pennies because dozens of companies can make them. Vaccines? Not even close. A vaccine like Pfizer’s mRNA COVID-19 shot isn’t just a mix of ingredients. It’s a tiny lipid nanoparticle carrying genetic instructions into your cells. That particle? Made from five specialized lipids. Only seven suppliers in the world make those. If one factory in Germany shuts down, the whole supply chain stumbles. You can’t just order more from Alibaba. There’s no off-the-shelf version. And that’s before you even start the manufacturing process. It takes six to twelve months to produce one batch. You need biosafety level 2 or 3 labs. You need temperature-controlled rooms. You need sterile fill-finish lines that cost $50 million each. A single production line can cost over half a billion dollars to build. No small company can afford that. No country without decades of experience can just start.Who Makes the World’s Vaccines?

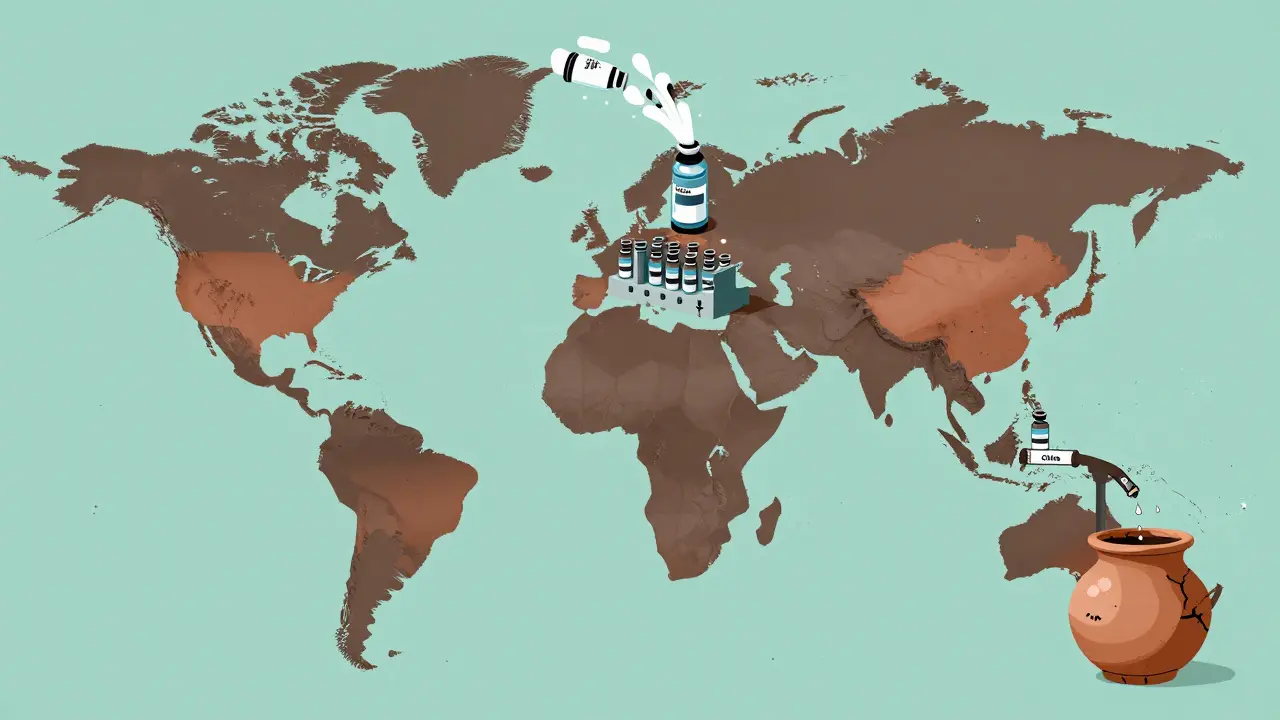

Five companies-GSK, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson-control about 70% of the global vaccine market. That’s $38 billion in 2020. These firms don’t just sell vaccines. They own the patents, the tech, the supply chains, and the regulatory relationships. But here’s the twist: India makes most of the world’s vaccines by volume. The Serum Institute of India alone produces 1.5 billion doses a year. It’s the largest vaccine maker on Earth. It made the AstraZeneca shot for less than $4 a dose, while Western companies charged $15-$20. Yet, even with that scale, India still imports 70% of its vaccine raw materials from China. That’s not independence. That’s dependency with a big factory. India supplies 60% of the world’s vaccines by volume. It provides 90% of the measles vaccine the WHO uses. It makes 40-70% of the DPT and BCG shots. But almost all of it is exported. Less than 10% stays in India for domestic use. When India stopped exports during its 2021 COVID surge, global supply dropped by half. Suddenly, the world realized: the backbone of global vaccine access was running on fumes.The Africa Paradox: Producing Nothing, Importing Everything

Africa has 1.4 billion people. It produces less than 2% of the vaccines it uses. The rest? Imported. From Europe. From India. From the U.S. In 2021, 83% of the 1.1 million COVID-19 doses delivered to Africa through COVAX went to just 10 countries. Twenty-three African nations had vaccinated under 2% of their populations. Meanwhile, African health ministers stood up at the WHO and said: “We make 60% of the world’s vaccines-but we import 99% of our own.” Why? Because building a vaccine plant isn’t like building a drug factory. It takes 5 to 7 years. It costs $200-500 million. It needs trained engineers, sterile environments, and a steady supply of ultra-pure lipids and cell cultures. Africa doesn’t have that infrastructure. It doesn’t even have the skilled workforce. The continent’s pharmaceutical industry is where Asia was in the 1980s-before India became the pharmacy of the world. The African Union wants to change that. Their plan: get 60% of Africa’s vaccines made locally by 2040. That will cost $4 billion. That’s a lot. But it’s less than what the U.S. spends on military drones in a year.

Technology Transfer? It’s Not as Simple as Sharing a Recipe

In 2021, the WHO launched a mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub in South Africa. BioNTech, the German company behind Pfizer’s vaccine, agreed to share its know-how. Sounds promising, right? It took 18 months just to get the first batch made. Why? Because BioNTech didn’t just hand over a PDF. They handed over a whole ecosystem. The South African team couldn’t find the right bioreactors. They couldn’t source the exact lipid nanoparticles. The machines they ordered from Europe were delayed by sanctions and export controls. Even the water for cleaning equipment had to meet pharmaceutical-grade standards-something no local supplier could provide. By September 2023, the hub finally produced its first mRNA vaccine. But it can only make 100 million doses a year. That’s less than 1% of global demand. This isn’t a failure of will. It’s a failure of structure. You can’t transfer a vaccine like you transfer a software license. You need factories. You need supply chains. You need regulators who understand biological manufacturing. You need money. And you need time.The Price of Equity

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, negotiates prices with manufacturers for low-income countries. They got the pneumococcal vaccine down to $3.50 a dose. But that’s still $3.50 per child. Multiply that by hundreds of millions of children. And then realize: that’s not a discount. It’s a concession. The manufacturer still made a profit. Compare that to generic drugs. When a drug like atorvastatin goes off-patent, prices drop 80-90%. Within a year, you’ve got 20 companies making it. Competition drives prices to near-zero. Vaccines don’t work that way. There’s no competition. There’s no rush to copy. The barriers are too high. So prices stay high. And the poorest countries pay the most in relative terms. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, health workers received doses that expired in two weeks. No cold chain. No refrigerated trucks. No way to use them. That’s not a production problem. That’s a distribution and equity problem. And it’s happening right now.

The U.S. and China: Who Controls the Raw Materials?

The U.S. FDA reported in October 2025 that only 9% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturers are in the U.S. China has 22%. India has 44%. That’s not just a supply chain issue. It’s a national security issue. During the 2021 Indian COVID surge, the U.S. restricted exports of key vaccine raw materials. India’s production stalled. Global supply shrank. Suddenly, the world realized: if you rely on one country for the building blocks of life-saving vaccines, you’re one crisis away from disaster. The U.S. is now running a pilot program to fast-track generic drug approvals if they’re made in America. It’s a start. But it’s for pills. Not vaccines. And even that won’t fix the real problem: the lack of global manufacturing capacity.What’s the Real Solution?

There’s no magic bullet. No patent waiver will fix this. No international pledge will fix this. What will fix this is investment. Real, sustained, long-term investment in manufacturing capacity where it’s needed most. India showed it’s possible. It scaled up during the pandemic. It made billions of doses. But it still depends on China for raw materials. It still needs Western tech for mRNA. It still can’t meet its own population’s needs without export restrictions. Africa needs to build. Not just one plant. Not five. But dozens. Across multiple countries. With shared supply chains. With training programs. With local regulators who can inspect and approve. And rich countries? They need to stop hoarding. They need to fund the factories. They need to let go of intellectual property control when it comes to global health emergencies. The WHO’s hub in South Africa is a good model. But it’s a drop in the ocean. By 2025, low- and middle-income countries will still be 70% dependent on vaccine imports. That’s not progress. That’s a system designed to fail. Vaccines are the most effective public health tool we have. But they’re also the most unequal. We can make them. We know how. But we haven’t chosen to share the means to make them.Why This Matters Beyond COVID

This isn’t just about the pandemic. It’s about every child who doesn’t get the measles shot. Every mother who loses her baby to tetanus. Every refugee camp without a single dose of cholera vaccine. If we can’t fix vaccine access now, we’ll face the same crisis again. Next time, it might be a new flu strain. Or a drug-resistant TB outbreak. Or a pathogen we haven’t even named yet. The tools exist. The science is there. The will? Not yet. We don’t need more promises. We need more factories. More trained workers. More local supply chains. More equity. Because when it comes to saving lives, there’s no such thing as a generic solution.Shanahan Crowell

Okay, but let’s be real-vaccines aren’t like ibuprofen. You can’t just throw some lipids in a blender and call it a day. It’s not a recipe, it’s a symphony-and half the instruments don’t even exist in most countries. We’re treating this like a software update when it’s a whole damn operating system.

And yeah, India’s the unsung hero here-making 1.5 billion doses a year while getting zero credit. Meanwhile, we’re over here hoarding boosters like they’re limited-edition sneakers. The system’s broken, not the science.

We need factories, not Facebook posts. Real investment. Real patience. Real humility.

Kerry Howarth

This is exactly right. Vaccines aren’t generic. They’re complex biological systems. Copying the formula is like copying a bird’s wing and expecting it to fly.

The real issue is infrastructure, not patents.

erica yabut

Oh, so now we’re pretending this isn’t a deliberate, capitalist-engineered scarcity? Please. The ‘manufacturing complexity’ narrative is the most elegant lie Big Pharma has ever sold. They could mass-produce mRNA vaccines in their sleep-if they weren’t busy pricing them at $150 a pop and patenting the damn air.

Let’s not pretend the lipid nanoparticles are ‘too hard to source.’ They’re sourced from seven companies because seven companies *own* the patents. It’s not a technical barrier-it’s a profit barrier. And you, my dear, are just repeating the corporate PR script.

Meanwhile, the WHO hub in South Africa? A token gesture. A PR stunt. Like giving a starving man a single crouton and calling it a banquet.

They don’t want equity. They want control. And you’re helping them sell it.

JUNE OHM

OMG I KNEW IT 😤

China is controlling ALL the raw materials. That’s why India’s supply chain collapsed. That’s why Africa can’t make anything. That’s why the U.S. banned exports. This is a BIOWEAPON STRATEGY. They’re letting poor countries die so they can control the next pandemic. 🚨

And don’t even get me started on the WHO. They’re just a puppet for Big Pharma. I bet they’re funded by Pfizer. I bet they’re all in on it. 😳

Someone needs to leak the documents. This is worse than 9/11.

Also, why do we still have vaccines? Why not just let nature take its course? 🤔

Philip Leth

Man, I’ve been to a few vaccine plants in Pune. It’s wild. You walk in and it’s like a sci-fi movie-robots, sterile rooms, people in full-body suits. And the chill? It’s colder than a Minnesota winter.

But here’s the kicker-most of the people running those plants? They’re from Kerala or Tamil Nadu. Trained by the government. Not by some Silicon Valley startup.

So yeah, India’s not just a factory. It’s a legacy. And we’re all depending on it. Funny how the world forgets that when they’re buying their boosters.

Angela Goree

Wait-so you’re telling me we’ve been lied to for 40 years? That ‘generic’ doesn’t mean what we think it means? That vaccines are some kind of magical unicorn that only five companies can make? That’s not just unfair-that’s treason!

And why is China supplying 70% of the raw materials? That’s not a supply chain-that’s a chokehold!

And don’t even get me started on the WHO. They’re all in on this. I bet they’re getting kickbacks from Pfizer. I bet they’re in cahoots with the CDC. This is a global scam. A global scam!

Someone needs to start a movement. We need to burn down the FDA. Burn it. All of it.

Tiffany Channell

Let’s dissect this logically. The post claims vaccines are ‘living systems.’ That’s scientifically inaccurate. Vaccines are biological products, not living organisms. The mRNA is inert until it enters cells. The lipid nanoparticles are synthetic. No life involved.

Further, the assertion that ‘you can’t copy a vaccine’ is demonstrably false. The Serum Institute has reverse-engineered AstraZeneca’s adenovirus vector. They’ve done it. Multiple times.

The real issue? Regulatory capture. The FDA, EMA, and WHO prioritize Western manufacturing standards to exclude emerging economies-not because it’s impossible, but because it’s inconvenient for incumbents.

Also, the claim that ‘no small company can afford it’ ignores the fact that 80% of vaccine production costs are in regulatory compliance, not capital equipment.

Stop romanticizing complexity. This is rent-seeking disguised as science.

Joy F

Ah, the myth of the ‘vaccine exception.’ The sacred cow of pharmaceutical exceptionalism. We’ve been conditioned to believe that biologicals are too complex, too fragile, too divine to be democratized. But isn’t that just a narrative to preserve monopoly rents?

Let’s zoom out. The entire global health architecture is built on a colonial framework: the Global North designs, the Global South manufactures, and the Global North owns the IP and sets the price.

The mRNA hub in South Africa? A performative gesture. A digital placebo. It’s like handing a starving child a picture of a sandwich and calling it ‘food sovereignty.’

And let’s not forget: the patent waiver debate wasn’t about access-it was about liability. Who gets sued when a ‘copy’ fails? The manufacturer? The donor? The WHO? The answer: no one. So they keep the status quo.

This isn’t about science. It’s about power. And power doesn’t yield without a fight.

Haley Parizo

Let’s talk about dignity.

Why is it acceptable for a child in Malawi to wait 18 months for a vaccine that a child in Boston gets in 18 days? Why is it acceptable that Africa’s health ministers stand in front of the WHO and say, ‘We make 60% of the world’s vaccines-but we import 99% of our own’-and no one flinches?

This isn’t a logistics problem. It’s a moral failure.

We treat vaccines like luxury goods instead of human rights. We hoard them like gold. We patent them like private property. And then we wonder why the world is sick.

There’s no technical barrier. There’s only a moral one.

And we’re all complicit.

Ian Detrick

Look, I get it. It’s complicated. But complexity isn’t an excuse. It’s a challenge.

India built a vaccine empire on grit, not magic. They didn’t wait for permission. They didn’t wait for patents to expire. They just… did it.

And now we’re acting like the solution is to give them a PDF and call it ‘technology transfer.’ That’s like giving a toddler a Formula 1 manual and expecting them to win the Monaco Grand Prix.

We need apprenticeships, not handouts. We need engineers, not lectures. We need decades of investment, not three-year pilot programs.

And yeah-maybe we need to let go of control. Maybe the world doesn’t need one center of power. Maybe it needs many.

It’s not about lowering standards. It’s about raising access.

Angela Fisher

I’ve been researching this for 3 years and I’ve found something terrifying.

Did you know that the lipid nanoparticles in mRNA vaccines are made using a chemical called ALC-0315? And guess who owns the patent? Moderna. And guess who controls the supply? A single company in Germany. And guess what happens when they shut down? Global supply CRASHES.

And here’s the worst part: the FDA knows this. The WHO knows this. But they won’t tell you.

Why? Because they’re being paid off by Big Pharma. They’re part of the cabal. They’re keeping you in the dark so you don’t realize vaccines are a trap. A trap to control the population. To keep you dependent. To keep you afraid.

And now they want to build more factories in Africa? That’s just the next step. To make it look like they care. But it’s all a lie.

I’ve seen the documents. I’ve talked to insiders. They’re coming for your children next.

Wake up. The truth is out there. But they don’t want you to find it.

Neela Sharma

My uncle worked at Serum Institute for 22 years. He used to say: ‘We don’t make vaccines. We make hope.’

We ship doses to 170 countries. We don’t get credit. We don’t get royalties. We don’t get to keep even one dose for our own families during the pandemic.

But we still made them. Because someone had to.

Now you want us to build factories in Africa? Good. Send your engineers. Send your machines. Send your money. Don’t send your pity.

We know how to do this. We just need you to stop standing in the way.

Shruti Badhwar

The structural inequity in global vaccine production is not accidental-it is institutionalized. The current framework privileges intellectual property rights over public health imperatives, creating a hierarchy where manufacturing capacity is geographically concentrated and access is contingent on economic power.

While India demonstrates scalability through volume and cost-efficiency, its reliance on imported raw materials underscores the fragility of this model. True sovereignty requires vertical integration: from lipid synthesis to cold-chain logistics.

The African Union’s 2040 vision is not aspirational-it is existential. The $4 billion investment required is not a cost-it is a dividend on human survival.

Patent waivers are symbolic. Capacity building is systemic. We must shift from charity to equity. From donors to partners. From dependence to autonomy.

Shanahan Crowell

Neela, you just said everything I’ve been trying to say for years.

‘We make hope.’ That’s the line that breaks me.

And yeah-don’t send pity. Send engineers. Send training. Send funding. Send trust.

India didn’t wait for permission. Why should anyone else?

Write a comment