Renal Dosing Calculator

Calculate Creatinine Clearance

Enter patient details to determine renal function and appropriate antibiotic dosing.

Results

When someone has kidney disease, giving them the same antibiotic dose as a healthy person isn’t just risky-it can be deadly. The kidneys don’t just filter waste; they clear drugs from the body. When they’re damaged, antibiotics build up. That buildup doesn’t make the drug work better-it makes it poison. Every year, thousands of hospital patients with kidney problems suffer avoidable harm because their antibiotic doses weren’t adjusted. It’s not a rare mistake. It’s a systemic failure.

Why Renal Dosing Isn’t Optional

Chronic kidney disease affects 37 million Americans. That’s one in five adults. Many of them end up in the hospital with infections-pneumonia, UTIs, skin abscesses. And every time they’re given an antibiotic, their kidney function must be checked. Why? Because 60% of commonly used antibiotics are cleared mostly by the kidneys. If those kidneys can’t keep up, the drug stays in the blood too long. That leads to hearing loss, nerve damage, seizures, or even sudden cardiac arrest.

Studies show that getting the dose wrong increases death risk by nearly 30% in pneumonia patients with kidney disease. In urinary tract infections, it’s 20%. These aren’t theoretical numbers. These are real people-older adults, diabetics, people on dialysis-who died because someone assumed their dose was fine.

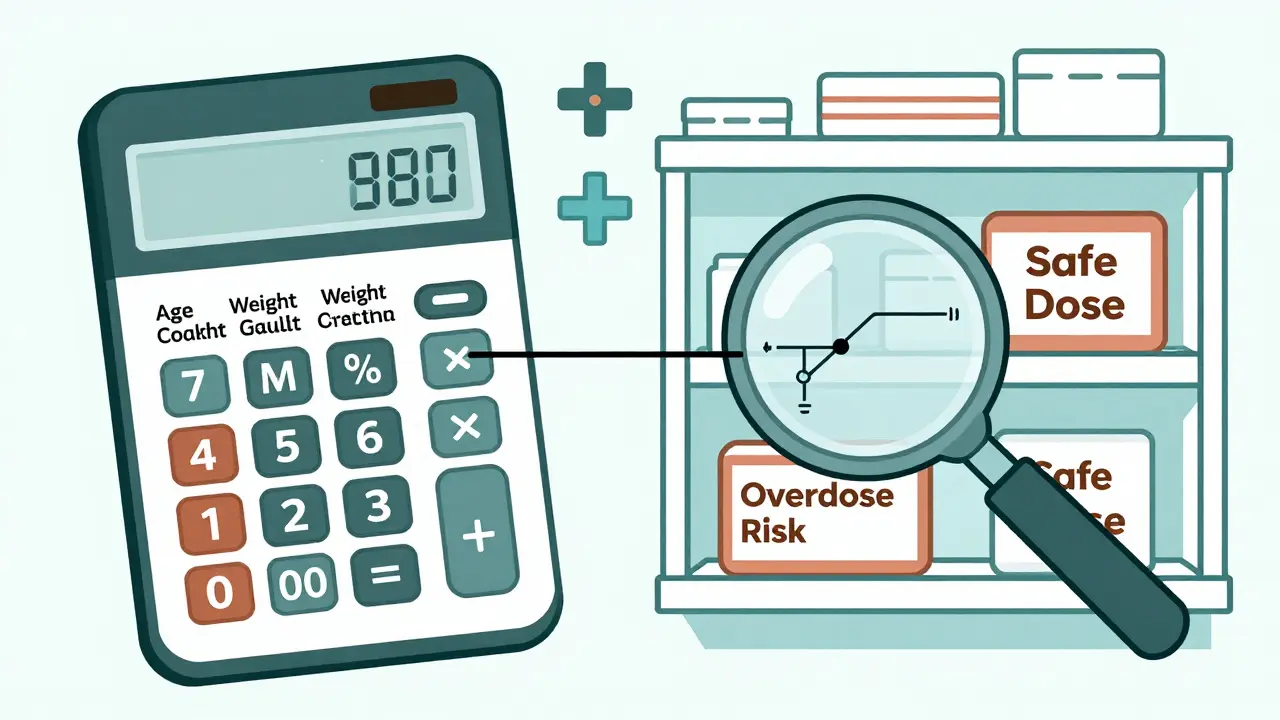

How Doctors Measure Kidney Function

The gold standard for figuring out how well kidneys are working isn’t a fancy scan or a blood test alone. It’s the Cockcroft-Gault equation. It uses four things: age, weight, sex, and serum creatinine. The formula looks like this:

CrCl = [(140 - age) × weight (kg)] / [72 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)] × 0.85 (if female)

That’s it. No machine. No app needed. Just a calculator and the numbers from the lab. Despite newer formulas like eGFR, Cockcroft-Gault is still the most trusted method for dosing antibiotics. Why? Because it includes weight. And weight matters-especially in obese patients, where using actual body weight instead of ideal weight leads to massive overdosing.

Here’s how kidney function is broken down for dosing:

- Normal: CrCl >50 mL/min

- Mild impairment: CrCl 31-50 mL/min

- Moderate impairment: CrCl 10-30 mL/min

- Severe impairment or dialysis: CrCl <10 mL/min

But here’s the trap: many doctors still use eGFR from lab reports and assume it’s the same as CrCl. It’s not. eGFR is better for tracking long-term kidney damage. CrCl is better for figuring out how fast a drug leaves the body. Mixing them up is a common error-and it’s dangerous.

How Antibiotic Doses Change With Kidney Function

Not all antibiotics need the same adjustments. Some are forgiving. Others are not. Here’s what happens with a few key ones:

Ampicillin/sulbactam: Standard dose is 2 grams every 6 hours. But if CrCl is below 15 mL/min? Drop to 2 grams every 24 hours. That’s an 80% reduction. Go too high, and you risk seizures. Go too low, and the infection won’t clear.

Cefazolin: A common surgical antibiotic. Normal dose: 1-2 grams every 8 hours. In severe kidney failure? Cut it to 500 mg to 1 gram every 12 to 24 hours. The window is wide, so underdosing is more common than overdosing. But even here, giving the full dose to someone on dialysis can cause muscle weakness or numbness.

Ciprofloxacin: An oral antibiotic often prescribed for UTIs. Standard: 500 mg every 12 hours. For CrCl 10-30 mL/min? Cut it to 250 mg every 12 hours. This is where mistakes happen most. Oral antibiotics are easy to prescribe. Doctors forget to adjust them. A 2019 study found 78% of dosing errors involved oral drugs like this.

Then there’s the outlier: ceftriaxone. Most guidelines say no adjustment needed-even in dialysis patients. Why? Because it’s cleared by the liver as well as the kidneys. It’s one of the few antibiotics that can be given at full dose regardless of kidney function. But not all guidelines agree. Some hospitals still reduce it. That’s confusion. And confusion kills.

Where Guidelines Clash-and Why It Matters

There’s no single rulebook. Different hospitals use different sources. The University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) says clarithromycin needs a dose cut if CrCl is under 30 mL/min. Northwestern Medicine says no change needed unless CrCl is under 50 mL/min. Which one do you follow?

This isn’t just academic. A 2023 survey of 1,247 clinicians found that 41% of pharmacists struggled to choose between conflicting guidelines. For ampicillin/sulbactam, one hospital might say 2 grams every 24 hours for CrCl under 15, while another says every 48 hours. That’s a 50% difference in daily dose. One patient gets a safe dose. The other gets underdosed-and the infection spreads.

Even worse: most guidelines ignore acute kidney injury (AKI). AKI can happen overnight after surgery, sepsis, or dehydration. Kidney function might drop fast-but bounce back in 48 hours. If you reduce the antibiotic dose right away, you risk treatment failure. If you don’t reduce it at all, you risk toxicity when the kidneys start recovering.

Dr. Jason Roberts, who led the landmark 2019 review, says: “We’re reducing doses too early in AKI. We’re treating it like chronic disease when it’s not.” He’s right. For antibiotics like ceftolozane/tazobactam, underdosing in early AKI leads to higher failure rates. But overdosing later leads to nerve damage. The timing matters as much as the dose.

Augmented Clearance: The Overlooked Problem

There’s another side of the coin. Not everyone with kidney problems has slow clearance. Some patients-especially young, healthy, critically ill people-have augmented renal clearance. Their CrCl is above 130 mL/min. Their kidneys are working overtime. That means drugs get flushed out too fast. The antibiotic never reaches a high enough level to kill the infection.

UNMC’s 2023 guidelines are one of the few that address this. They recommend doubling the dose of piperacillin/tazobactam to 2 grams every 4 hours for patients with CrCl over 130. Most other guidelines don’t mention it. So patients with sepsis and high kidney function get underdosed. They don’t get better. They die.

This is why relying on outdated protocols is dangerous. We’re not just adjusting for failure-we’re also adjusting for overperformance. Both sides need attention.

What Works in Real Hospitals

Some places have fixed this. Academic medical centers that use electronic alerts in their EHR systems cut antibiotic errors by 50%. Pharmacists who review every antibiotic order for kidney patients reduce adverse events by 37%. Hospitals that standardize on one guideline-usually KDIGO-see fewer mix-ups.

Here’s what actually helps:

- Use Cockcroft-Gault. Not eGFR. Not guesswork.

- Always check weight. Use actual body weight, not ideal.

- For IV antibiotics, give a loading dose if recommended. Vancomycin? Yes. Cefazolin? Usually not. Know the difference.

- For oral antibiotics, double-check the dose. It’s easy to miss.

- Use institutional protocols. Don’t rely on memory or outdated handouts.

- When in doubt, consult a pharmacist. They’re trained for this.

And if the patient is on dialysis? Don’t assume the dose is the same as for severe kidney failure. Hemodialysis removes some drugs, but not all. Some antibiotics are removed during treatment-so you give a dose after dialysis. Others aren’t removed-so you give the full dose before. It’s not intuitive. That’s why dialysis units need specific, written protocols.

The Future: AI, Monitoring, and Better Rules

Things are changing. The FDA now requires new antibiotics to be tested in patients with kidney disease. The European Medicines Agency does too. That’s progress. But we’re still behind.

Therapeutic drug monitoring-measuring actual drug levels in the blood-is still rare. Only 38% of academic hospitals do it. But by 2027, that’s expected to jump to 65%. For drugs like vancomycin and linezolid, this is life-saving.

Some hospitals are testing AI tools that auto-calculate doses based on lab values, age, weight, and diagnosis. Pilot programs show promise. But they’re not perfect. They still need human oversight.

The big gap? Acute vs. chronic kidney disease. The KDIGO 2023 update is finally addressing this. Until then, the rule should be: Don’t reduce antibiotics in AKI unless the patient is truly anuric or in shock. Wait 48 hours. Recheck creatinine. Adjust then.

Because the real enemy isn’t kidney disease. It’s the assumption that one-size-fits-all dosing works. It doesn’t. And people are paying the price.

Do all antibiotics need dose adjustments in kidney disease?

No. About 60% of commonly used antibiotics require adjustment, but some-like ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and linezolid-don’t need changes even in severe kidney failure. This is because they’re cleared by the liver or have wide safety margins. Always check a reliable source before assuming a drug needs adjustment.

Is eGFR good enough for antibiotic dosing?

No. eGFR estimates glomerular filtration rate for long-term kidney health, but it doesn’t account for body weight or muscle mass well. The Cockcroft-Gault equation is still the gold standard for dosing because it includes weight and sex, which directly affect how fast drugs are cleared. Relying on eGFR alone can lead to under- or overdosing.

What if a patient is on dialysis?

Dialysis removes some antibiotics but not others. For drugs removed by hemodialysis (like ampicillin, vancomycin, cefazolin), give the dose after dialysis. For drugs not removed (like metronidazole, doxycycline), give the full dose before dialysis. Always check whether the drug is dialyzable. Don’t guess. Use institutional protocols or pharmacist guidance.

Can I use the same dose for obese patients?

No. Many dosing formulas use ideal body weight, but for antibiotics, actual body weight is often more accurate-especially for fat-soluble drugs. However, for drugs cleared by the kidneys, using actual weight can lead to overdosing in very obese patients. The safest approach is to use adjusted body weight: Ideal weight + 0.4 × (Actual weight − Ideal weight). Always verify with a pharmacist.

Why do some guidelines say to reduce doses while others don’t?

Guidelines differ because they’re based on different studies, institutions, and interpretations. UNMC provides detailed dosing for augmented clearance and AKI; Northwestern includes CRRT adjustments. KDIGO tries to be global and conservative. Always use your hospital’s approved protocol. If none exists, default to KDIGO and consult a clinical pharmacist.

Marc Bains

Man, I've seen this go wrong so many times in the ER. A 72-year-old with CKD gets cipro for a UTI, same dose as someone with perfect kidneys. Next thing you know, they're in delirium, twitching, and the team is scrambling to figure out why. It's not rocket science-check CrCl, adjust the dose, done. But so many docs just click 'standard dose' and move on. We're talking life or death here, not a suggestion.

And don't even get me started on weight-based dosing in obese patients. Using actual body weight for vancomycin? That's how you turn a treatment into a toxicity cocktail. Ideal body weight, adjusted body weight-know the difference or stop prescribing.

Kelly Weinhold

Okay but can we just pause for a second and appreciate how wild it is that we still use a 1970s formula like Cockcroft-Gault in 2025? Like, we have AI that can predict heart attacks from EKGs, but we're still asking nurses to manually plug numbers into a calculator? I get it-it works, and it’s cheap, but come on. There are apps now that auto-calculate CrCl from the EHR. Why aren’t we forcing that into every order set? It’s not hard. It’s just laziness wrapped in tradition.

Also, shoutout to the nurses who catch these errors before the med goes in. You’re the real MVPs.

Kimberly Reker

One time I saw a patient on hemodialysis get a full dose of gentamicin because the resident didn't check the dialysis schedule. They ended up with permanent hearing loss. Not a single person on the team noticed until the patient started asking why the birds outside were so loud-because they couldn't hear their own voice anymore.

It's not just about the math. It's about culture. If you don't make renal dosing a habit, not a checklist item, people will keep forgetting. We need to treat it like checking for allergies-not optional, not extra, just part of the flow.

Eliana Botelho

Wait, so you're telling me we're still using Cockcroft-Gault and not eGFR? Are we in 1998? eGFR is literally in every lab report now. It's right there next to creatinine. Why are we pretending the old formula is better? It's not. It's outdated. And don't even get me started on the 0.85 multiplier for women-like, why are we still gendering kidney function? It's not 1972. This is just medical sexism dressed up as science.

Also, who even uses weight in kg anymore? We're in the US. Half the staff is still using pounds and guessing. This system is broken by design.

calanha nevin

Renal dosing errors are among the most preventable causes of iatrogenic harm in hospitalized patients. The Cockcroft-Gault equation remains the gold standard for antibiotic dosing due to its inclusion of weight, a critical variable often omitted in eGFR-based estimations. Failure to adjust for renal impairment results in elevated drug concentrations, leading to ototoxicity, neurotoxicity, and increased mortality. Adherence to established guidelines is non-negotiable.

Lisa McCluskey

Just wanted to add-when the patient is on dialysis, timing matters. Give the antibiotic after the session, not before. That’s the rule for most renally cleared drugs. But I’ve seen it done both ways and no one bats an eye. It’s not just about the dose-it’s about when you give it. Small thing. Huge difference.

owori patrick

Back home in Nigeria, we don’t even have creatinine tests in half the clinics. We guess. We use history-'he looks sick, he’s old, maybe cut the dose in half.' It’s not ideal but it’s survival. I wish we had the luxury of formulas. But I’m glad someone’s talking about this. We need this info everywhere, not just in fancy US hospitals.

Russ Kelemen

There’s a deeper question here: Why do we treat kidney function like a static number? It’s fluid. A patient can go from CrCl 45 to 15 in 48 hours with sepsis. We’re still using a single lab value from 24 hours ago to make a life-or-death decision. That’s not clinical reasoning. That’s algorithmic thinking.

What if we started treating renal dosing like we treat blood pressure-reassess every shift? Maybe then we’d stop killing people with good intentions.

Diksha Srivastava

I work in a rural clinic in India. We don’t have eGFR calculators. We don’t even have reliable creatinine machines. We use a printed chart we laminated in 2012. But we’ve saved lives with it. Simple, visual, hung on the wall. Maybe we don’t need fancy tech. Maybe we just need better systems that work in the real world-not just in teaching hospitals.

Sidhanth SY

My dad’s on dialysis. Got amoxicillin for a sinus infection. Dose was doubled because 'he’s got an infection, needs more.' He ended up in the ER with seizures. Turned out the dose was for someone with normal kidneys. He’s fine now, but I’ll never forget the look on the nurse’s face when she realized what happened. She said, 'We always do it that way.' That’s not a system. That’s a tragedy waiting to happen.

Sarah Blevins

Interesting. The post ignores the fact that many antibiotics like linezolid and daptomycin are not renally cleared. By overemphasizing renal dosing, this article may inadvertently cause clinicians to underdose drugs that require full dosing in renal failure. A misleading narrative.

Jason Xin

So we’re using a 50-year-old formula because it’s 'trusted'? Cool. Next we’ll be using leeches for hypertension. Meanwhile, the EHR has a built-in CrCl calculator that auto-populates based on lab values. But nope. Let’s keep doing manual math like we’re in a 1980s hospital drama. I’m sure the patients appreciate the nostalgia.

Donna Fleetwood

Y’all are overcomplicating this. Just make it a mandatory alert in the EHR. If CrCl is under 50, pop up: 'Renal adjustment required for this antibiotic. Click here for guidance.' Done. No thinking. No guessing. No excuses. We do it for allergies. Why not for kidneys? It’s not hard. It’s just not prioritized.

Melissa Cogswell

For vancomycin, always use ideal body weight unless BMI >30. Then use adjusted. I’ve seen people get 3g doses because they weighed 150kg. That’s not treatment. That’s a death sentence.

Diana Dougan

Wow. So the solution to killing people with antibiotics is... more math? Groundbreaking. Next you’ll tell us fire is dangerous if you don’t check the gas line. I’m sure the 10,000 nurses who’ve been doing this for decades are just waiting for a Reddit post to tell them how to do their job.

Write a comment